By Dr. Tom Palmer

I grew up in a Friends (Quaker) Church in Iowa Yearly Meeting where I heard many sermons. I’m not sure that I listened to a lot of sermons, at least to the point where I remember what was said. But my parents made sure I was there. Then I became a pastor and preached for nearly fifty years. And I’m not sure I remember many of my own sermons. But I believe deeply in the importance of preaching. What role does preaching have in a Friends Church?

A couple of words jump out at me. They reflect what I believe should be our uniqueness in the field of homiletics and worship: humility and Spirit-inspired.

Let’s do some looking back at where we have come from. Preaching or public oratory is found throughout the Bible. Moses had a hard time speaking but with Aaron’s help the word of freedom went out. David, Solomon, and the Prophets gave great sermons. Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, Peter on the Day of Pentecost, Paul throughout his journeys- all point to powerful, Spirit-led preaching. Hear the Great Commission in Mark 16:15: “Go into all the world and PREACH the GOSPEL to every creature.” In 1 Corinthians 2:1-5, we hear of preaching not “in lofty words or wisdom” but “in the power of God.” Like Paul, we come “in weakness and in fear and in much trembling” to proclaim the Gospel with power. Humility and Spirit-empowered preaching!

In his late teens, George Fox sought spiritual insight from preachers. He was disappointed because preachers had become dry and scholarly. The government of England in the 1600s appointed the clergy. They were educated at Oxford and Cambridge and sought out the prestigious pulpits. George called them “hireling shepherds” with little concern for the sheep, their parishioners. One pastor lost his temper as George accidentally stood on a flower in his garden. Various ones counseled him to take up tobacco, sing psalms, join the army, or get married; all suggested ways to deal with the hunger of his heart. After several years of searching, George heard a voice that said, “There is one, even Christ Jesus, that can speak to thy condition,” and when he heard it his heart “did leap for joy!”

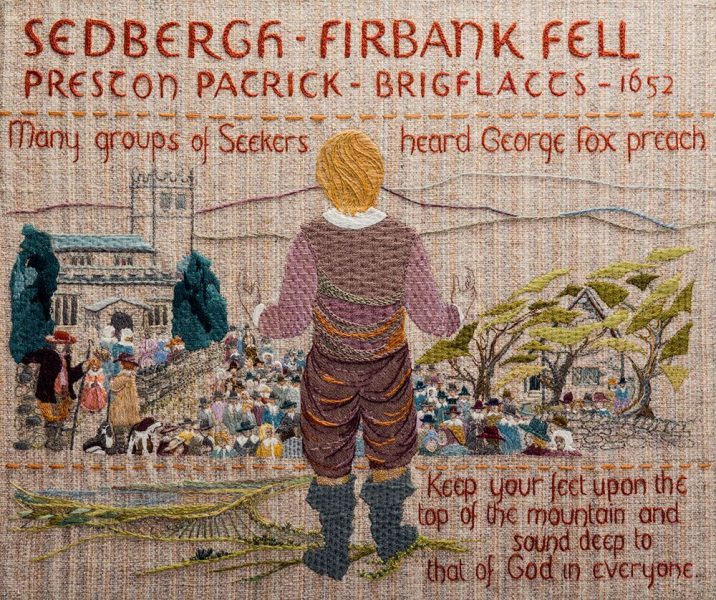

From that encounter, England would be turned upside down. George and his followers would stand up and interrupt sermons or go outside and preach after the sermon was over. This was seen as anti-government and heretical, so they were thrown in prison all over the country. George, William Penn, Margaret Fell, Issac Penington, Robert Barclay, and others were not trained preachers. One definite observation is that this preaching was impromptu, perhaps reactionary. There were not three points and a poem. Normally they did not organize their thoughts ahead of time but depended on the Holy Spirit and the power of God (like the Apostle Paul).

From the 1652 experience where Fox saw “a great people to be gathered” to 1690 over 100,000 people called themselves “Quakers” in England. But in the 1690’s this experiment in “Primitive Christianity Revisited (Wm. Penn’s 1696 book)” took an ominous turn. An overreaction to the formalism and sterility of the established church, anything that resembled human effort or planning was considered evil, part of the unregenerate human nature. The “Age of Quietism” began and lasted for 130 years, nearly killing off the Friends movement.

Friends met in silence and even got to the point of condemning anyone who spoke or read scripture. No music of any kind was allowed. There was one Quaker meeting that was proud of the fact that no one spoke in meeting for worship for twenty-two weeks. The joy and preaching of those early Friends were nearly lost. As “Publishers of Truth” they kept the Truth to themselves, and the missionary zeal nearly left us. “Go into all the world and preach the Gospel” changed to “come and sit in silence.” There were some great leaders during that period such as Penn, Elizabeth Fry, Laura Haviland, and John Woolman. Other leaders ignored the teaching of scripture and began to cause a major divide in Friends as the Hicksite and Wilburite splits occurred.

But when the Spirit is blocked in one setting, He will break forth elsewhere. John and Charles Wesley brought revival fires to England and on to America. Camp meetings and new churches were built across the growing nation. Some have speculated that if Friends had held onto their fire and passion for the Truth, the Wesleys would not have been needed or would themselves have been Quakers. But again, Spirit-led preaching became used by God in powerful ways.

The Holy Spirit did a new work (or a visiting of an old) in our movement. In February of 1877, a revival broke out among Friends in the Bear Creek meeting in Iowa, which was characterized by numerous days of preaching, weeping, confession, singing and even stepping over the seats to get to the altar. The conservative Friends declared that this event “had killed the Society of Friends.” The split between programmed Friends and unprogrammed (or silent) Friends began.

Preaching became a vital part of our yearly meeting and Friends across the nation. The following years ushered in our time of greatest growth and missionary efforts. Our membership grew to 12,289 by 1892 – Iowa Yearly Meeting’s largest ever! Our members reached out and started three other yearly meetings: Nebraska, Oregon, and California.

But Friends preaching may have become like any other Protestant denomination. Our aversion to “Oxford and Cambridge” educated clergy caused us to not have schools for training preachers. Those Friends who could go on for further education went to institutions with little appreciation for Friends doctrine and history. Another challenge that has become more evident in recent years is that pastors in Friends Churches come from other traditions and know little about our history.

In his excellent, Preaching the Inward Light, Michael Graves analyzes early Quaker rhetoric and evaluates the few sermons that we have remaining from 350 years ago. Those preachers were definitely preaching in “the power of God.” These impromptu messages came after waiting in silence. Graves concludes:

“Impromptu preaching poses extreme rhetorical challenges to anyone sufficiently brave (or foolish) to attempt it. The pressures on the minister are formidable, especially when the hearers are expected to listen carefully for signs that the preacher may have gone beyond her or his inspiration. In early Quaker meetings, the tension between silence and sound, between the passive and the active, must have been especially challenging for fledgling ministers, as judged by their journals…On the other hand, to speak on occasion as God’s oracle elevated the preaching task and gave language extra weight, an importance it might not have had in other preaching contexts (pg. 312).”

Here our theology of worship and Christ’s presence must come into play. If Christ is the “Present Teacher and Lord” as Fox proclaimed, then preaching comes out of the humility of waiting. We sit together with “The Presence in the Midst” (a 1916 painting by J Doyle Penrose). Jesus may empower the pastor who has prayerfully prepared a sermon to stand and proclaim the Good News or it may come from individuals waiting on the Spirit. Either way, humility and Spirit-inspired messages are essential.

Elton Trueblood, perhaps our most famous theologian, said that we must come prepared to be silent or to be ready to speak as the power of God comes upon us. Most protestant denominations see the sermon as the high point of the service. In Friends worship it should be as well, but the sermon may come from someone(s) other than the pastor and should come out of humble waiting on the Holy Spirit. Many years ago, a Friend from the unprogrammed branch of Quakerdom shared her concern with me. She said their silent meeting suffered because unprogrammed so often meant unprepared. Is that any different from my programmed meeting? Most of us come unprepared and definitely unwilling to think of sharing during open worship. We have bought into the model of American Christianity where we come on Sunday to be entertained and fed.

On the 300th anniversary of the founding of the Friends Church (1952), Trueblood gave the opening address at this celebration in Oxford, England. This year, 2024, we celebrate the 400th anniversary of George Fox’s birth. His words seem appropriate for our time and George’s birthday.

“The Friends in the summer of 1652, actually believing that Christ had come again to be their teacher, evidently lived day by day in triumphant and infectious mood similar to that described in the Book of Acts…. Our present meetings, of whatever type, are a poor substitute for what was going on 300 years ago. They sang, they laughed, they suffered gladly, they loved mightily…The double mark of the renewal of Primitive Christianity, initiated by Fox, was the spiritual high tension, on the one hand, and the continual outreach, on the other…The inner intensity would have been mere spiritual self-indulgence, if Friends had hugged their experience to themselves, but this they could not do. They preached in churches, they preached at fairs, they preached in prison… Judged by this standard, contemporary Quakerism is guilty of treason of a great dream. Our generation supposedly avoids over-pushing, but what this masks is really fear of dedication…. The Quaker movement must change…because today it is not good enough…The hour is late.”

I hope to glean from many more Spirit-led messages from God’s humble servants. Our world needs what Friends have to offer. May we offer it freely to a hungry, thirsty world.

Dr. Tom Palmer is a retired pastor in Iowa Yearly Meeting. He grew up on a dairy farm in Grinnell, Iowa. Tom graduated from William Penn University, Asbury Theological and Bethel Seminary. His Doctor of Ministry thesis at Bethel was “An Analysis of the Church Planting Strategy of Iowa Yearly Meeting.” He and his wife Jan had the joy of planting two churches. Together they have two daughters and three grandchildren.